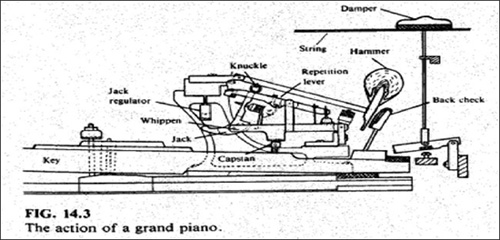

Italo’s Dreams’ Pianos- Calvino : Cotsonas :: Living : Weight 6 September 1985 The bed here is not Italo’s but belongs to no one. It is starched crisp and next to it Esther worries her handkerchief. Twisting it and twisting it between her hands she will have it threadbare before the week closes its eyes to not wake up, and like the cells of skin falling from her fingers, this week gets lost in the maze of time, becomes duplicated by another younger and fresher week, so similar, yet so absolutely different, that they can never be the same, and only differentiate when they conclude at their cancerous ends. Italo is not well. His mind, the life in it, has become crowded. If that is too abstract, let me tell you that, at the least, a bear dances on a ball in a clown’s hat there. Let me just say that riding a bike there serves no purpose. You cannot stay on it. Many shoulders rush together there, and the feet below the shoulders will not stop should you fall. You will be trampled in the city in Italo’s head, but you will not die. There is no death in the Italo’s head, but life only. Existence, or a non-existence. An example: a bird, more specifically a cardinal, is not currently dwelling in Italo’s considerations, but that is not to say that the cardinal has perished, but that there is simply, at this moment in the city in the Italo’s head, not a cardinal, but instead, a basket. Then, a basket full of apples. Then, apples on a wooden floor. Then, apples on a red wooden floor. Then, a door that opens into the house with the red wooden floor. Then, a small divot worn in that door by the latch whose duty it is to keep the door locked. In that locked room, a room filled to the ceiling with books, Italo selects one volume in particular, a yellow book concerning physics, and he sits in a leather chair (he describes it as ratty and so it is) by a window whose window pane’s thick lead paint has begun to chip and fall to the red floor. He reads the physics book from cover to cover, which is without a legible title, but is something that stems from Italo’s youth. See, Italo has forgotten about the basket he had only taken into consideration moments ago, but, on the contrary, he has not forgotten about all baskets. They are in his head if he finds them. Stockpiled. But, recently, and here is the problem, there are too many things, of which baskets are some, stockpiled in his mind, and he cannot let them out. The exit from this city in his head is one long traffic jam, and all the roads lead further and further inward. The people that live here, too, they cannot get out and they rush and collide with the numerous items in the city. Together, the items and the people, make the music in this city, and the city is very loud. And together, the items and the people are the city, and traditionally, the city changed to suit the rhythms of itself, and these tunes played were pictures, too, most of them, though, some were sounds and smells. They recalled Italo’s life and so Italo lets the senses be, because he is their vessel, while the people who are the city, dream of their crowded paths to freedom. Italo dreams with them, and, because his time is almost over, (the city’s jam is killing him), he chooses a handful of thing to dream about, namely pianos. The water does not suffocate Italo but he can feel its weight while he swims. The bottom of the ocean dances in greens. The sand does not move, fish move, a silver school of them hovering above the bottom in the expanding and wiggling reflections of light, but the ocean floor does not appear to move. It gets moved in and over by the things that can move: light and fish. In the ocean with the light and the fish is a grand piano, but one of a million estranged grand pianos lingering at the bottom of the sea. The strings curl from under the lid and the dampers have been nibbled. The pedals are buried in the gray silt of the ocean’s floor and the bench has settled on its side. Swimming down and righting the bench Italo raises the lid to gaze upon the piano’s vitals. He closes the lid before tapping the keys. The very faint sound of what could be stones clicking together is what he hears when the hammer strikes on broken wire. He presses his index finger on the G sharp key again and again, bending lower to hear the hammer knock against the lid of the piano. A shark, attracted by the noise, cruises Italo, and Italo swims off before the sound of stones can remind him of the road he was walking down the day that he met his wife, Esther. Italo’s hands are huge and he slams them into the keys at a pace that can only be considered frightening, as he plays Rachmaninoff’s 3rd on a hill as the wind moves through the grass and over Esther’s shoulder. Her hair unfurls from its bun. It is warm and the sun lingers behind the boughs of an apple tree over laden with fruit. The apples on the ground smell of apples. Italo dreams a dream of pianos. He rationalizes the dream while dreaming. Puts it to a science and a study. Italo understands the pianos are the subconscious construct of metaphor for the crystalline, or structural, systems Italo’s psyche has placed on any number of things he has experienced throughout his life, and in the dream, to accompany this rationale, there is a chart for Italo in which all parts of the piano’s mechanisms are shown in order that he might understand the resulting sequence of events from the pressing of any single one of the piano keys:  Back Check Capsten Damper Hammer Jack Jack Regulator Key Knuckle Repetition Lever String Whippen All of these words mean little or nothing to Italo without the drawing, but in the drawing he can discern how the operation, the pressing of a single key, brings into motion all of the small pieces. He sees how the simple pressing of a key is not simple at all if one wishes to produce a sound, but merely the first action in several simple actions making up a complex whole that causes the desired hammering of the piano string and the resulting sound waves via the vibration of said string. Italo studies the chart until he firmly grasps the concepts of the piano’s workings, and as he understands that pianos, and therefore the drawing of pianos to be the subconscious construct of metaphor for the crystalline, or structural, systems of his own psyche, he begins to replace the parts of this reaction with parts of his own life. Back Check/ a baseball cut with a razor knife in the Cuban street. Capsten / a hole in the floor of his Italian veranda in which a mouse he named Domenico lived. Damper / the hospital bed in which he lies dreaming. Hammer / Battle Name: Santiago. Jack / Eighteen years old playing snooker in the Turin Brothels. Jack Regulator / World War II. Key / the three times the Nazi party pretended to kill his father. Knuckle / the knuckle of his right hand connected to the index finger in which Italo grasps the hospital sheets believing it is a chart filled with piano parts. Repetition Lever / the knuckle of his left hand connected to the index finger in which Italo grasps the hospital sheets believing it is a chart filled with piano parts. Strings / Baron in the Trees Whippen / a nickname for his wife, Esther, at the age of forty. Plink.1 These components have put each other into motion by the simplest acts resulting in the music (here again the psyche employs metaphor) of Italo’s life, namely: the ineffable feelings, the sounds and qualities created by physical mechanism but otherwise inexplicable by any one word. But then, Italo realizes that the sound is not accounted for in the particularities of the chart, and he knows that the damper will not always be the hospital bed, but also a clamshell he crushed into a Brooklyn sidewalk after eating black beans and rice near Fort Greene Park. Perhaps, he thinks, that particular instance is the damper of a different key. If this is true, then all of the keys on the piano, of which there are 36 black keys and 52 white, must have binary labels in which they emblemize one aspect of Italo’s life. This thought process results in all of the keys becoming more than binary labels in which they are Key, in and of the essentialist parameters of Key; Key as a priori, and also of Other, because they are more than that which is being named, and simultaneously never those names, ever, because they are imaginations, memories. There can be no one-to-one comparison beyond the exactness of this particular dream piano’s working mechanisms. For instance, if the dream author states that the piano in his dream is the very same piano played by Sergei Rachmaninoff as he slaughtered his own First Symphony in D Minor resulting in his mental breakdown and a three year hiatus from composing, it is simply not true. But the piano does not tell him this. It is merely a piano, after all. In a dream. Esther and Italo rumble over the loose cattle guard sending the heifers and calves bawling into the dry ravine where a bull wallows in his own urine and stops momentarily to snort the dust. The truck in which they ride is forest green and rusted out along the side panels. Apples fall out of the truck bed. The tailgate was taken from them in the morning when they stopped for a cup of café Cubano. They are glad to be out of the city. Esther sees the ivory first because she is looking for rabbits scurrying along the edge of the road. The block looks like a broken slab of Doric; a great Greek ruin, left to be covered in the Italian ryegrass growing through the barbed wire fences. When Italo brakes, he sees the ivory block is actually a bench for a weathered and legless piano abandoned in the ditch to the side of the road. The ryegrass sprouts its purple heads out from under the piano and, in the wind, strikes against the blackness and gloss of the damaged lid. Italo lightly presses the gas pedal and the truck ambles into a pine grove where, on three consecutive trees, silver telescopes hang from rusted rail spikes. The telescopes rock easily in the wind. Esther looks through one while standing in the bed of the truck. On a hill, far across the field, a Marsican brown bear, Ursus arctos marsicanus, is walking in the shade of the trees. Italo bites into, and then swallows, his apple, the core, the stem, the seeds, everything. 19 September 1985 Italo dies in the evening from a cerebral hemorrhage, but before this his city becomes weightless, has the sound of weightlessness, whatever that may be. Before this Italo dreams he was a piano being played by Sergei Rachmaninoff’s enormous hands. Italo dreams he is an apple being eaten by his wife. Italo dreams that he drives his index finger into the same ivory key over and over for an hour and then stops when an unidentifiable child throws a stone through his front room window. He dreams he is that child. He dreams he is that stone. His dreams are windows. His dreams are red doors with welcome mats. His dreams are cities populated with things. His dreams apply logic. He writes his dreams on paper and then dreams about writing. His dreams are his life. His life, his dream. He equates imagination to dreams, to thoughts and to constructs. They are all tools to make a music, and these tools are all made from simple forms in the earth or the air: wood, iron, water. Italo, before he dies, is a man. A man is an assemblage of oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and these have everything to do with his dreams. And these have everything to do with pianos. And these have everything to do with everything, even death. Or, if you wish, pianos have nothing to do with any of it. |

|

||||

| Copyright © 1999 – 2024 Juked |

|